The Stakes of Diasporic Framing in Contemporary Asian Art

Written by Sophie Becquet, McGill University

Edited by Rachel Barker

In contemporary Asian art, the concept of “diaspora” has played a crucial yet contested role in how artists are understood, exhibited, and historicized. As artists navigate lives shaped by migration and cultural adaptation, the term “diasporic” is often used to distinguish their practices from those of artists who remain in their country of origin. Yet this term also risks flattening diverse experiences under a single label, suggesting a shared point of origin or orientation that may not align with the artists’ own sense of self or creative intent. This paper explores whether diaspora remains a useful or adequate category for thinking about the work of contemporary Asian artists who live and create across multiple geographies.

Rather than accepting or rejecting the term outright, I consider what is gained and potentially lost when artists are framed through the term “diaspora,” and reflect on how meaning might be more responsibly negotiated. Drawing on the work of theorists Margo Machida, Jane Chin Davidson, Rhacel Parreñas and Lok Siu, Saloni Mathur, and Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner, I examine how the term has evolved in both art historical and curatorial discourse. I also consider alternative terms to assess whether they offer more flexible and precise frameworks in certain situations. Ultimately, I argue that while some form of differentiation could be necessary to recognize the specific histories and conditions of artists shaped by migration, any such terminology must be approached with attention to context, institutional framing, and artistic agency.

Among the most influential voices in theorizing Asian American visual culture, art historian Margo Machida offers a historically grounded and politically engaged understanding of diaspora in her book Unsettled Visions: Contemporary Asian American Artists and the Social Imaginary (2008). Machida treats diaspora as a position shaped by lived histories of migration, U.S. imperialism, and racialization. The term’s value lies in revealing how difference is produced through structures of exclusion and resistance, rather than simply marking cultural difference. Her framework is rooted in the activist legacies of the 1960s and 70s, a period when artists mobilized identity as a form of collective political assertion. As she writes, “In this period, an Asian American political and social consciousness emerged among many visual artists, who made a deliberate effort… to use the power of art and visual culture to enunciate an imaginative identification with a panethnic conception of Asian commonality.”[1] Machida sees this tendency as a deliberate political strategy to resist marginalization by claiming visibility and solidarity across diverse Asian communities. Through panethnic framing, artists challenged dominant narratives that had rendered them invisible or exotic, making identity a source of collective power and cultural reimagining.

Figure 1: Installation view, Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 1995. Photo: Barbara Economon.

Machida is attentive, however, to how the institutional use of “diaspora” can lead to its depoliticization. Once adopted by museums and academic frameworks, terms like “Asian American” and “diasporic” risk becoming mechanisms of classification, emphasizing ethnic legibility over artistic complexity. She warns that Asian American artists often face an art world “in which work addressing issues of identity is associated with a ‘politics of victimization’ and a coercive political correctness—or, conversely, with complicity in relegitimizing unstable ethnic and racial categories that uphold the majority culture’s order of knowledge.”[2] This institutional dynamic, Machida argues, is often shaped by a deeper ideological structure that she calls the “guest/host paradigm.” She writes: “Asians are perceived as the perpetual guests (some of whom have clearly overstayed their welcome), whereas Anglo Americans are implicitly cast as beleaguered, sorely abused hosts… as guests, [Asians] are required to play by the house rules; if they are not prepared to do so, then, as the statement suggests, they shouldn’t be here in the first place.”[3] In this framework, Asian presence is tolerated only under conditions of deference and compliance.

The 1994 exhibition Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art, first held at the Asia Society Galleries in New York, exemplifies both the promise and pitfalls of this institutional framing (fig. 1). Curated by Margo Machida, Vishakha N. Desai, and John Kuo Wei Tchen, the exhibition brought together work by Asian American artists from diverse backgrounds to address questions of bicultural identity. It aimed to challenge stereotypes and assert the vitality of Asian American artistic production, positioning these artists within contemporary art discourse. Yet despite its ambitions, Asia/America also risked reinforcing the very dynamics Machida critiques. Rather than being received on their own terms, the artworks were often interpreted as expressions of grievance or cultural dysfunction. For some audiences, this reinforced the view that these artists were failing to be good guests: too critical, too wounded, too demanding of sympathy. Rather than fostering solidarity, such framing could provoke discomfort or judgment, subtly positioning the artists as undeserving of empathy. This tension reveals how exhibitions, even those organized with care and political commitment, can be constrained by the institutional expectations they seek to challenge. Machida’s broader concern is that identity-based inclusion, when shaped by institutional expectations, can flatten difference and weaponize visibility against the very subjects it claims to support. To resist this, Machida proposes an interpretive methodology she calls “oral hermeneutics,” a dialogical approach that centres the artist’s voice, intentions, and relationship to community. Meaning, in her view, should be co-produced through collaboration between artists and scholars, rather than imposed from curatorial or institutional scripts.[4]

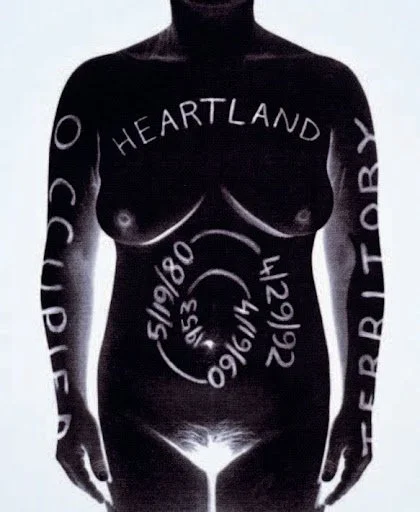

Fig. 2. Yong Soon Min, Photograph of artist’s body with inscriptions from Defining Moments series, 1992. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 16 in.

Machida’s theoretical concerns about institutional framing are grounded in close analysis of specific artworks from the Asia/America exhibition. One such example is Yong Soon Min's photographic series Defining Moments (1992), in which the artist inscribes her own body with layered references to personal, Korean, and Korean American histories (fig. 2). For Machida, this act of visual self-inscription functions not as a representation of fixed identity but as an invitation for shared acts of remembrance, what she describes as a mode of interpretation “aiming to achieve something appreciably different… through jointly generating knowledge with producers of art.”[5] Min’s work stages diaspora as an ongoing negotiation of history and memory, enacted materially and dialogically.

A different but equally powerful example is Marlon Fuentes’s Bontoc Eulogy (1995), which Machida discusses as a cinematic critique of how institutional framings, particularly within anthropology and world’s fair exhibitions, construct the diasporic subject as an object of spectacle (fig. 3). Through a fictionalized narrative of a Filipino American narrator searching for his grandfather, who was allegedly displayed at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, Fuentes exposes the ways diasporic identity is shaped by imperial technologies of display. He describes his film as a “highly layered meditation of cultural abduction and social voyeurism,” in which archival footage and voiceover narration are used to simulate ethnographic “authority”—only to destabilize it by revealing the constructed nature of such narratives.[6] These curated spectacles, as Machida notes, not only shaped Western perceptions of the Filipino “Other,” but also circulated back to the Philippines, where their representational logic was internalized by later generations.[7] In this way, Bontoc Eulogy reveals how diasporic subjectivity is not only framed externally through institutional mechanisms, but also absorbed and contested from within. The film complicates any fixed or unified narrative of diaspora and reinforces Machida’s broader argument that artistic practice can challenge and unsettle frameworks of racialized difference.

Fig. 3. Marlon Fuentes, film still from Bontoc Eulogy, 1995.

These two works demonstrate Machida’s key claim that diasporic artists do not merely reflect historical experience, but actively reshape how that history is told, remembered, and visualized. In doing so, they confront and reconfigure the institutional narratives that have long defined the boundaries of the cultural understanding of Asian diasporic subjects.

These concerns about how institutions frame diasporic Asian artists as knowable through predetermined narratives of identity are not limited to the American context. They echo more globally in the ways artists from Asian backgrounds are positioned within international exhibitions, biennials, and pavilions, settings where identity becomes a curatorial device. While Machida emphasizes the racialized guest/host dynamic within U.S. cultural institutions, art historian Jane Chin Davidson extends the critique to the global art world, where categories such as “Chineseness” operate in structurally similar ways to “diaspora.”

In Staging Art and Chineseness (2020), Chin Davidson critiques how global biennials and national pavilions continue to frame artists through essentialized cultural categories—particularly “Chineseness.” She focuses less on diaspora per se and more on how adjacent terms like “Chineseness” function similarly as labels imposed through curatorial systems that prioritize national or ethnic identification. This process, she argues, is neither neutral nor accidental. “The ‘staging’ of the artist in the context of the exhibition is always-already representing nation and culture through the biennial’s entrenched meanings, categorization, signifiers, and symbolism of display,” she writes.[1] Like the term “diaspora,” “Chineseness” here operates less as a self-defined identity than as an institutional construct, shaped by the demands of cultural consumption on a global stage.

Chin Davidson’s critique draws on theorists like Rey Chow to show how “Chineseness” has historically been tied to orientalist imaginaries that oscillate between cultural fetishization and civilizational exclusion. For much of the twentieth century, she notes, the term was viewed as politically suspect through its implication in Western projections of racial otherness.[2] However, in the wake of poststructuralist and postcolonial theory, “Chineseness” has been reframed as a floating, performative signifier, one that must be read through shifting geopolitical contexts. Chin Davidson argues that contemporary artists often find themselves navigating exhibition frameworks that demand easily recognizable markers of identity through what she calls the “symbolism of display” embedded in global biennial structures.[3] In these contexts, artworks are frequently curated to represent nation or ethnicity, even when artists may seek to trouble or evade such clear-cut associations. Rather than rejecting identity, Chin Davidson observes that many artists respond by subverting the visual codes expected of them, unsettling assumptions about cultural authenticity and coherent representation. Chin Davidson’s core insight is that identity in the global art world is curated, staged, and often constrained by exhibitionary logics. Her intervention aligns with Machida’s critique of ethnic overdetermination, but shifts the frame from American racial politics to transnational display. Together, their work reveals that identity terms like “diasporic” or “Chinese” are actively constructed through institutional frameworks that carry political and aesthetic stakes.

While Machida and Chin Davidson foreground cultural politics and curatorial mediation, the volume Asian Diasporas: New Formations, New Conceptions (2003), edited by sociologist Rhacel Salazar Parreñas and cultural anthropologist Lok C. D. Siu, shifts attention to diaspora as a structurally embedded condition shaped by global capitalism, imperialism, and racialized migration regimes. The editors define diaspora as “an ongoing and contested process of subject formation embedded in a set of cultural and social relations that are sustained simultaneously with the ‘homeland’ (real or imagined), place of residence, and compatriots or coethnics dispersed elsewhere.”[4] This definition foregrounds the simultaneity and relationality at the core of diasporic experience.

Parreñas and Siu outline three defining features of diaspora: (1) displacement from the homeland within an unequal global political and economic system; (2) a dual sense of alienation and affiliation with both host and home countries; and (3) a collective consciousness shared with dispersed coethnics across multiple locales.[5] These dynamics, they argue, are sustained through everyday practices, making diaspora not only a condition but an ongoing set of negotiations lived out through material and imaginative means.

Importantly, the editors insist on the plural—“Asian diasporas”—to signal internal heterogeneity and to resist essentialist or homogenizing tendencies.[6] The project is intentionally comparative and multiscalar: it brings together place-specific, cross-ethnic analyses (such as the racialization of Filipinos and Indonesians in Taiwan) alongside ethnic-specific, transnational ones (such as the experiences of Chinese migrants in Panama or Korean adoptees across the Pacific).[7] This dual focus allows the volume to interrogate both local dynamics of racialization and broader transnational flows, illustrating how Asian diasporic identities are formed through complex intersections of class, gender, colonial histories, and geopolitical positioning.

The editors further distinguish diaspora from transnationalism. While both involve cross-border linkages, transnational migrants maintain connections primarily between home and host societies. In contrast, diasporic subjects are embedded in a wider terrain of dispersed coethnics and are shaped by a shared sense of collective identity and history. As they explain, “some migrants… are better described not as diasporic but as transnational because they maintain relations only to the home and host societies and do not share a connection or history with compatriots living in other locales.”[8] For Parreñas and Siu, diaspora functions as an intellectual and political project. They argue for its potential to extend the coalitional spirit of Asian American studies beyond national borders by forging translocal and transethnic alliances. Yet, they are also attentive to power differentials and the tensions that arise in building solidarity across uneven terrains. Their aim is not to erase those tensions, but to confront them directly as part of the project of achieving social justice and representational equity.

This structural perspective foregrounds diaspora as a condition forged through global inequalities, shifting the analytic emphasis from cultural identity to systems of power and mobility. Yet while Parreñas and Siu highlight how diasporic formations emerge within these structural contexts, the question remains: how do such conditions alter the disciplines that seek to represent and interpret them? This question is explored in The Migrant’s Time: Rethinking Art History and Diaspora (2011), edited by art historian Saloni Mathur, which treats diaspora as a force that unsettles art history’s epistemic foundations, moving beyond understanding it as merely a representational subject.

While Mathur’s edited volume does not focus specifically on Asian diaspora, it makes a crucial contribution to understanding how diasporic conditions unsettle art historical method itself. In her introduction, Mathur clarifies that the goal of the collection is not to define an “art of diaspora” or an “art of migration” but to explore how migration and displacement demand new modes of art historical inquiry.[9] Rather than treat diaspora as a thematic category that can be added to the canon, she argues it must be understood as a force that reshapes the discipline’s core assumptions about geography and temporality.

Drawing on historian Ranajit Guha’s opening essay, also called “The Migrant’s Time,” Mathur expands this premise by emphasizing that the migrant does not simply experience geographic displacement, but rather a “temporal maladjustment,” defined by the “tragic disjunction” between past and present.[10] In this framework, diaspora unsettles the linear, developmental timeframes that have long structured art historical narratives. Mathur argues that to reckon with the diasporic condition is to grapple with multiple, coexisting temporalities and to rethink how modernity, nationhood, and artistic production are sequenced and understood. Rather than seeing diasporic art as belated or derivative of Western traditions, the volume insists on attending to its distinctive temporal logic which bends time and fragments chronology.

This temporal reorientation is articulated in art historian Kobena Mercer’s essay, “Erase and Rewind: When Does Art History in the Black Diaspora Actually Begin?” which offers a powerful illustration of how diaspora challenges the temporal assumptions of art history. Mercer critiques the field’s “present-ist understanding of intercultural exchange,” arguing that diaspora is a historical condition that rewrites how we understand the entire arc of modernity rather than a purely contemporary phenomenon.[11] He writes that “art history has been oblivious to the interactive dialectic of cross-cultural borrowing—the give-and-take of expropriation and appropriation as a back-and-forth process that constitutes one of the basic conditions of modernity in the visual arts.”[12] For Mercer, reconceptualizing diaspora requires undoing the “monologic assumption that there was only one story to tell about the relationship between modern art and modernity and only one way to tell it.”[13] This means looking beyond the dominant timelines and geographies of art history to recover the long histories of displacement, circulation, and cross-cultural entanglement that have shaped modern and contemporary visual cultures. In this sense, Mercer calls for art historians to “erase and rewind,” rereading the past from a different starting point that foregrounds difference as a foundational condition of the modern.

Recent scholarship in curatorial studies has likewise pushed for frameworks that resist essentialist or grievance-based readings of contemporary Asian art. In the edited volume Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions: Connectivities and World-making (2014), art historians Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner bring together a range of perspectives that reconceptualize exhibitions as active agents in shaping transnational imaginaries. Rather than relying on national or diasporic classifications, the volume foregrounds curatorial strategies that emphasize relationality. As Antoinette writes in her introduction, the essays “emphasise the connective medium of art itself as a vital key in forging connection for the region and between the region and the world… for the imagination and generation of new ways of being and belonging in the world at large.”[14] This emphasis on connection invites curators and scholars to engage with contemporary Asian art as a space of world-making. In this way, Antoinette and Turner contribute to a growing body of thought that seeks to reframe the curatorial and interpretive strategies used to engage with artists shaped by migration.

Diaspora, as this paper has argued, should be re-situated as a methodological challenge rather than a classificatory endpoint. The tendency for diasporic exhibitions [1] to centre narratives of trauma or alienation risks flattening the range of meanings artists intend to convey. When exhibitions perform grievance, they limit interpretation to a narrow emotional register. By soliciting empathy or moral concern, they obscure other dimensions of the work, including its formal experimentation or affective complexity. Margo Machida offers a crucial alternative through her concept of “oral hermeneutics,” a dialogic methodology grounded in conversation between artists, communities, and curators. This approach allows meaning to emerge relationally, rather than being imposed by institutional narratives. It invites us to shift the focus away from whether “diaspora” is a useful category, and toward more collaborative interpretive practices that ask how artists’ situated experiences inform their work, and how institutions can be accountable to those positions. Such a shift also raises important questions about aesthetic consequences. As Jane Chin Davidson observes, the institutional expectation that diasporic artists render identity visibly or legibly may shape not only how their work is read but how it is made, pressuring artists toward recognisable notions of difference or authenticity. Many artists respond by developing strategies that push back against these expectations, creating works that are deliberately opaque, fractured, or layered. Saloni Mathur further expands the discussion by treating diaspora not as a thematic supplement but as a historiographic force that reorients the temporal and spatial coordinates of art history. In parallel, Rhacel Parreñas and Lok Siu frame diaspora as a set of unstable social relations marked by displacement and transnational connectivity, rather than as a stable identity category. Finally, Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner extend these debates into the curatorial realm, proposing that exhibitions can serve as platforms for world-making, emphasizing artistic and geopolitical connections over categorical coherence. Together, these scholars offer an approach to contemporary Asian art that resists reductive framings and opens space for interpretive methods rooted in dialogue, relationality, and formal complexity. In this view, diaspora becomes less a label to contain art, and more a generative site from which artists and curators alike can rethink the structures of meaning and representation.

Endnotes

[1] Jane Chin Davidson, Staging Art and Chineseness: Politics of Race and Cultural Production in Global Perspective (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 10.

[2] Chin Davidson, Staging Art and Chineseness, 11.

[3] Chin Davidson, Staging Art and Chineseness, 10.

[4] Rhacel S. Parreñas and Lok C. D. Siu, Asian Diasporas: New Formations, New Conceptions (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007), 1.

[5] Parreñas and Siu, Asian Diasporas, 1-2.

[6] Parreñas and Siu, Asian Diasporas, 7.

[7] Parreñas and Siu, Asian Diasporas, 3.

[8] Parreñas and Siu, Asian Diasporas, 7.

[9] Saloni Mathur, “Introduction: The Migrant’s Time,” in The Migrant’s Time: Rethinking Art History and Diaspora, ed. Saloni Mathur (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), viii.

[10] Mathur, “Introduction,” vii.

[11] Mathur, “Introduction,” xii.

[12] Kobena Mercer, “Erase and Rewind: When Does Art History in the Black Diaspora Actually Begin?” in The Migrant’s Time: Rethinking Art History and Diaspora, ed. Saloni Mathur (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 22.

[13] Mercer, “Erase and Rewind,” 19.

[14] Michelle Antoinette, “Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art,” in Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions: Connectivities and World-making, ed. Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner (Canberra: ANU Press, 2014), 23.