Conversations with the Moon: How Anishinaabe Artist Caroline Monnet Challenges Settler Time with Film

Written by Céleste Dugas, McGill University

Edited by Annabella Lawlor and Marie Frangie

Caroline Monnet’s IKWÉ is available for viewing, in its entirety (00:04:45), on the artist’s website.

Introduction

Indigenous cinema is a powerful means of representing and celebrating Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and becoming. Anishinaabe artist Caroline Monnet’s short film IKWÉ (“woman”) enacts Indigenous temporalities that challenge and transcend settler conceptions of time[1]. Monnet visualizes the reciprocal connection between Indigenous women’s bodies and the land and waters that sustain them. She highlights forms of intergenerational knowledge transmission that escape settler notions of linear time, reclaiming Indigenous women's key roles in protecting the cyclical nature of life on Earth. Through the film, she further transmits this knowledge to the audience, with the trusting demand that viewers take environmental responsibility forward into their future.

Considering that Indigenous storytelling traditions also challenge linear schemes of time, carrying teachings relevant in any time and context, my analysis will follow the guidance of Monnet’s narrative structure to honour the wisdom in its weaving. I will begin by placing Mark Rifkin’s theoretical framework of settler time in conversation with other scholarly contributions, notably Kyle Powys Whyte’s discussion on time as kinship and Salma Monani’s work on Indigenous cinema temporalities.

Understanding Settler Time and Indigenous Temporalities

In Beyond Settler Time, Mark Rifkin argues that the notion of a universally shared timespan contributes to the continuous erasure of Indigenous stories, knowledge, and self-determination.[2] The colonial imposition of a singular, shared time frame discredits Indigenous intergenerational, cyclical, and relational epistemologies and ontologies. Rifkin affirms that the separation of land and time is a colonial construct; Indigenous conceptions of time are rather rooted in the motions of their material and environmental realities. “Settler time” also entails a dichotomization of past and present, with modernity as a driving ideal for settler statehood and identity that discards past histories rather than holding them in conversation. This linear frame also constructs Indigenous Peoples as static tokens of primitiveness against which settlers can measure and nurture their imaginary of modernity. Paula Gunn Allen, a Laguna Pueblo poet, denounces North American settler culture’s propensity for forgetting, in contrast to Indigenous value systems that foremost honour the knowledge of individuals connected with ancestral and traditional worldviews.[3] Irrefutably, the modernization theory, which offers a linear model towards exponential capitalist growth, entails always looking forward and never back. Its extractive methodology also demands the domination of humans over all other forms of life. In the words of Kanienʼkehá:ka (Mohawk) scholar Audra Simpson, the settler state, sustained by the exponential demands of its capitalist apparatus, follows a “death drive.” The settler state is a mechanism that requires the thorough and systemic annihilation of Indigenous Peoples, land and knowledges.[4] While the legitimacy of settler sovereignty requires eliminating Indigenous political governance, a capitalist economy oversees the escalating extraction, commodification and consumption of land and its diverse forms of life. The striving for modernity, measured against a past deemed static and undesirable, is thus concurrently a striving for death.

Modernity also requires considering contemporary Indigenous life, like land and non-human life, as inanimate or bound to disappear. As Rifkin argues, representations of Indigenous Peoples that recognize their existence in the present often include them in settler conceptualizations of modernity that ultimately seek the assimilation and erasure of their traditional knowledge. Affirming Indigenous Peoples’ “modernity” within colonial time frames mirrors the politics of inclusion that restrict Indigenous self-determination to the legal and territorial boundaries of the nation-state. Rifkin argues that there is, in fact, no singular experience of temporality; temporality is instead woven subjectively depending on subjects’ “frames of reference.”[5] To share an experience of temporality—to observe simultaneity with another application of time—subjects must share frames of reference. Understanding temporalities as webs that find their pulses in lived and relational realities allows the refusal of settler colonial territorial and temporal boundaries. Rifkin thinks of Indigenous expressions and experiences of time beyond settler conceptualizations as forms of “temporal sovereignty.”[6]

Temporal sovereignty is a politics of refusal. It entails refusing to bind Indigenous representation to the colonial death drive by nurturing and visualizing the sustenance of Indigenous lives, land, and knowledges in the future. Salma Monani discusses the role of Indigenous cinema in enacting Indigenous conceptions of time and space[7]. She points to Potawatomi philosopher Kyle Powys Whyte’s description of Indigenous intergenerational time as “living alongside future and past relatives simultaneously as we walk through life.”[8] This notion of time, in which past, present, and future are not separated but intertwined and mutually informative, resonates with Allen’s emphasis on remembrance as a key source of knowledge in Indigenous communities. Intergenerational temporalities challenge settler time because they honour and follow the cyclical rhythms of life on Earth. Indigenous knowledges are grounded in the dynamic relational webs of ecosystems; they follow their pulse as frames of reference, rejecting abstractions of universal time. As Monani argues, cinema opens space for relational temporalities. Knowledge from the past can take form in the present. Indigenous cinema also challenges settler time, as the audience must adopt Indigenous frames of reference to experience simultaneity. In other words, a film screening is a privileged moment in which viewers are invited to step inside Indigenous temporalities and walk alongside past and future relatives.

The film IKWÉ follows an Indigenous woman (Ikwé) in a conversation with Grandmother Moon. In Anishinaabe thought, she is a relative whose sacred knowledge is particularly meaningful to women’s lives and bodies.[9] IKWÉcarves a privileged space of communion between a woman and her ancestor that escapes linear time.[10] The conversation does not necessarily happen in the past, present, or future, but everywhere at once; it happens when we look inside for Ikwé as a frame of reference or when we look up at the moon.

Intergenerational Time and Women’s Cyclical Ties to Moon and Water

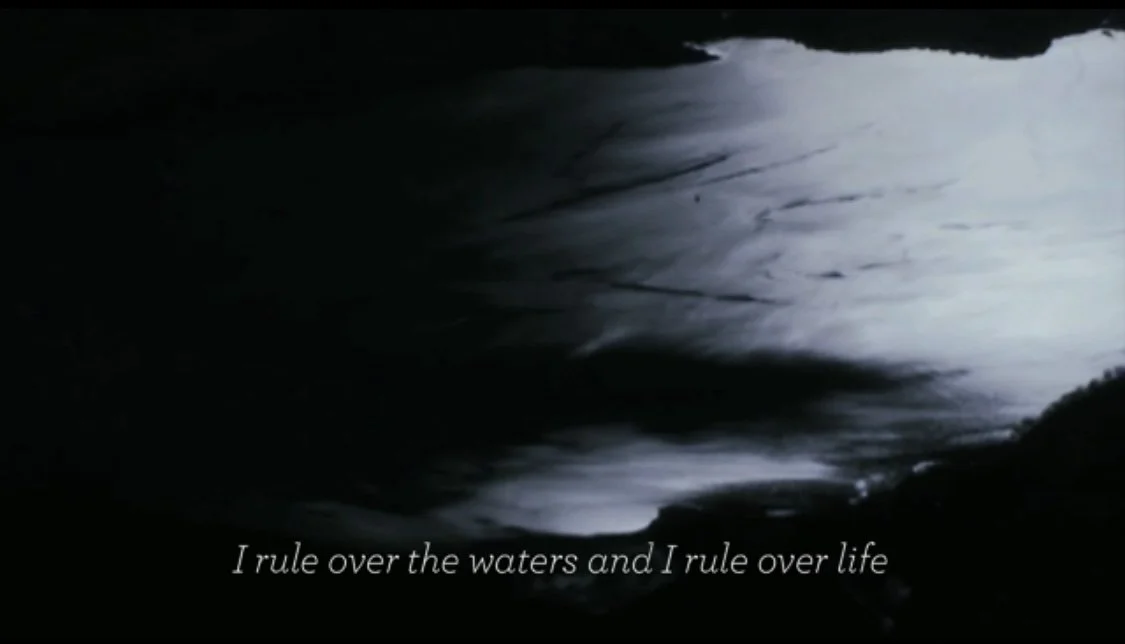

A woman is lying down in a fetal position. Monnet’s voice arises in French: “I close my eyes and free my spirit.” An eye seems to look at her from above. “The whispers of the moon tell me the ways,” Ikwé says, “She runs and stops and waits to see if I understand.” On the screen, large bodies of water scroll by. Another voice arises, in Cree: “Do you remember me? I am Grandmother Moon. I rule over the waters, and I rule over life. Something is calling you. Something old. From a very long time ago.” Ikwé’s face appears on the screen. It is half-lit. “Like the moon, you are the water keeper,” says Grandmother Moon. “You are giver of life.” In the dark space that covers the other half of Ikwé’s face, another shot of her face appears. This time, it is bright red (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Marking the first half of IKWÉ is Monnet’s tribute to the relational bonds between women (Ikwé), the moon, and water. Each shot is carefully crafted to visualize manifestations of these reciprocal connections. For instance, the screened bodies of water are bathed in a dim, dark blue light and seen from above, to raise the viewer to the moon's perspective (Figure 1). Their juxtaposition with the words of Ikwé denies the audience the possibility of separating the human narrator from other forms of life shown on screen. The audience is led to accept that the relational bonds between these life forms characterize and define them.

Figure 1. Grandmother Moon comes to Ikwé, from IKWÉ, directed by Caroline Monnet (Winnipeg Film Group, 2009), 0:01:10. https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9.

In Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe epistemologies, the moon is revered as a force that governs all water movement on Earth.[11] Women are considered to have a precious connection with water. From the water of their womb to the water of their blood, women’s intimate intertwinement with life is embodied as, and enacted through, water. Grandmother Moon controls the movement of water, and water gives life through women’s bodies. Kanienʼkehá:ka (Mohawk) activist Katsi Cook writes:

[Grandmother Moon’s] constant ebb and flow teaches us that all Creation is related, made of one breath, one water, one earth. The waters of the earth and the waters of our bodies are one… Our milk, our blood and the waters of the earth are one water, all flowing in rhythm to the moon. [12]

In Anishinaabe relational worldviews, the moon and water, Nokomis Giizis and N’bi in the Ojibwe language, are relatives with responsibilities towards each other and humans. In her work on understanding relationships between Anishinaabek, Nokomis Giizis and N’bi, Susan Chiblow echoes the teachings she received about Anishinaabek naaknigewin (Indigenous knowledge or natural law). According to Anishinaabek naaknigewin, women—because they carry and observe the cyclical pulse of life—are responsible for ensuring that N’bi can continue to bring forth life in all of Creation. Grandmother Moon reminds women of their responsibilities in natural law.[13] In IKWÉ, Grandmother Moon’s visit to Ikwé occurs within the natural laws that govern their relationship and mutual responsibilities. Grandmother Moon reminds Ikwé of who she is by telling her, “Like the moon, you are the water keeper. You are giver of life.”[14] In doing so, she immerses Ikwé in the cyclical motions of natural law. She is both an ancestor and a guide, unfurling behind, before and alongside Ikwé’s footsteps.

This sequence manifests multiple temporalities. In Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee cosmologies, the lunar cycles are key frames of reference for measuring time.[15] The moon represents continuous cycles of rebirth; she renews herself every 28 days, in sync with women’s menstrual cycles. The natural order that upholds these cycles does not have a beginning or end, but rather exists in the well-being of relations between life forms. As Anishinaabe Grandmother Sherry Copenace explains, “This knowledge indicates how Anishinaabek naaknigewin is as old as the beginning of time but just as relevant today.”[16] The circular and relational temporalities of Anishinaabek naaknigewin unravel in parallel to settler time. To observe and enact them, we must become conscious of their frames of reference. As Ikwé declares in the film, the moon “runs and stops and waits to see if I understand.” She always waits for those who remember to tend to their relationship with her.

The first half of the film presents unfolding engagement in tending to her relationship with Grandmother Moon. She begins this process in her body: she lies in a fetal position (Figure 2). On the one hand, Monnet may use this image to refer to the bond between the moon and women’s reproductive cycles and powers. On the other hand, it is meaningful for Ikwé to find herself returning to the womb; she attunes herself to the moon’s rhythm of birth and rebirth. She begins where life begins: in the waters of her body, which is also her mother's and her grandmother’s bodies. In discussing the primacy of remembrance for accessing ancestral Indigenous knowledge, Allen points to the wisdom in gynarchical lineages. “Your mother's identity is the key to your own identity,” she explains.[17] Failure to remember our maternal lines is a failure to know ourselves. She recalls the Haudenosaunee Creation story of Sky Woman:

The Iroquois trace their origins to the descent of Sky Woman, who gave birth to a spirit daughter. When that daughter died giving birth to her twin sons, Sky Woman flung her body into the sky where it became the moon… For so powerful was the spirit woman's being that even in ‘death’ she continued to live.[18]

Figure 2. Ikwé lies in a fetal position, from IKWÉ, directed by Caroline Monnet (Winnipeg Film Group, 2009), 00:00:15. https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9.

In Haudenosaunee perspectives, death is viewed as a transformation of life, rather than an end.[19] Conversing with the moon entails entering a relationship with the lines of women who came before us and continue to live in our embodied knowledge. Grandmother Moon calls on Ikwé to remember her relations and to centre herself in the ancestral knowledge they carry: “Something is calling you,” she flags, “Something old. From a very long time ago.”[20] She invites Ikwé in shared temporality with her ancestors. The last shot of this sequence represents Ikwé in attunement to her lineage and to the moon; the blue half of Ikwé’s face resembles a half-moon. The imbrication of another half-face demonstrates that Ikwé comes to inhabit herself (Figure 3). Grandmother Moon’s call will guide Ikwé towards using her attunement with life to continuously challenge the colonial death drive.

Figure 3. Ikwé inhabits herself in remembrance, from IKWÉ, directed by Caroline Monnet (Winnipeg Film Group, 2009), 00:02:03. https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9.

Time as Kinship and Indigenous Resurgence

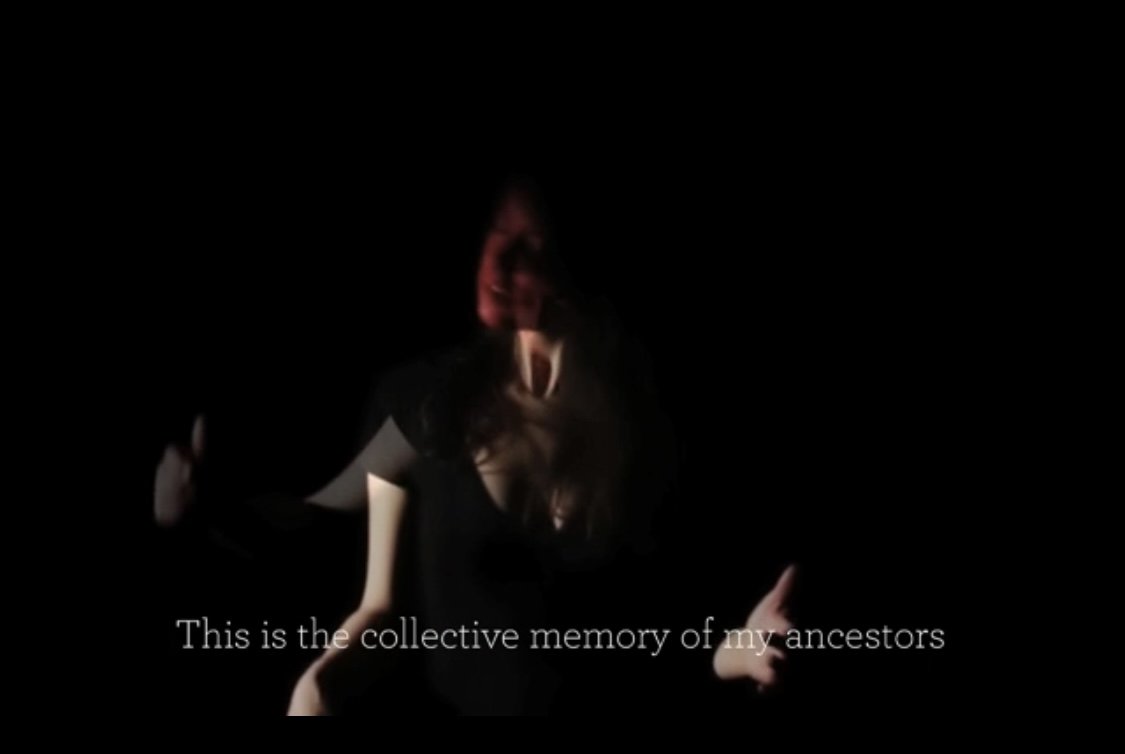

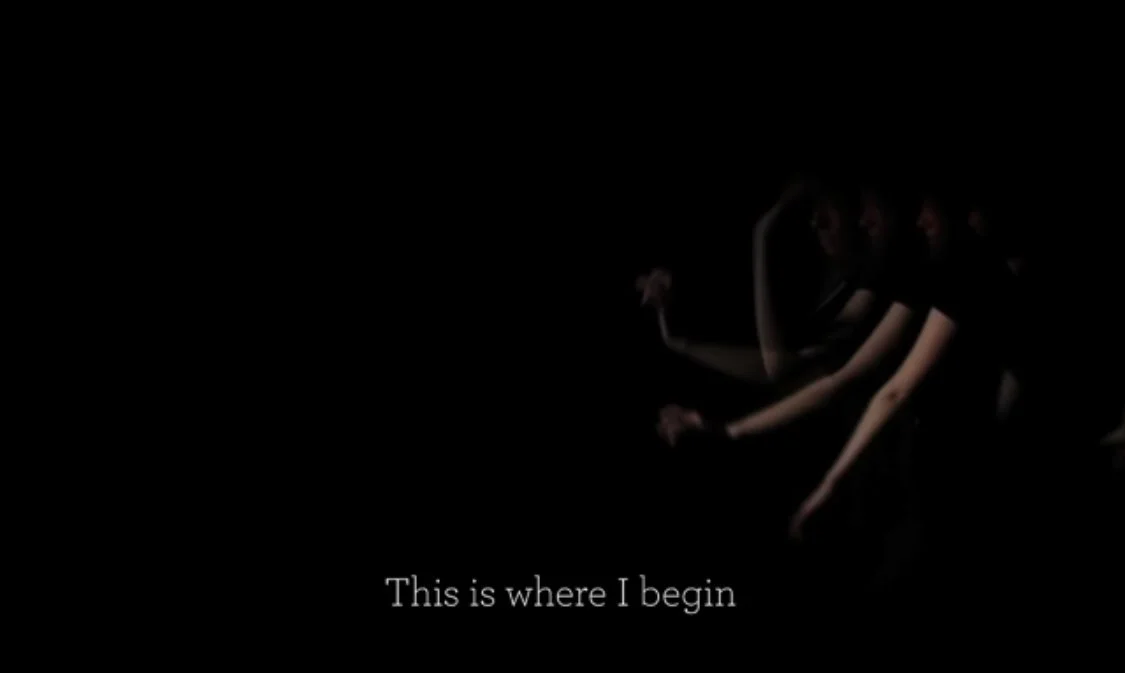

Ikwé’s red face turns to the camera and stares. “It has never been more important to hear our grandmother’s stories,” she says. Grandmother Moon speaks: “Grandmother has come to tell you something. My strength has left me because the lights of the Earth are too bright.” On the screen, city lights appear. Ikwé appears, standing. Her face is still red. She shakes her limbs. “This is the collective memory of my ancestors,” she says, “and it is a glue to my being” (Figure 4). Slowly, the movements become synced, like a dance. “A new life force fills me like fresh air,” she says, “and inspires me to love and create.” In a last movement, she raises her head suddenly and looks forward. “This is where I begin” (Figures 4 and 5).[21]

Figure 4. Collective memory sticks to Ikwé’s body, from IKWÉ, directed by Caroline Monnet (Winnipeg Film Group, 2009), 00:03:05. https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9.

The second half of IKWÉ turns to the mutual responsibilities that define Ikwé’s relationship with life. In his work on kinship time, Kyle Powys Whyte argues that Indigenous temporalities allow individuals to uphold their responsibility towards natural systems, as opposed to settler linear time frames. Whyte describes kinship as relations grounded in an ethic of mutual care and responsibility. Time, he argues, can be measured and understood through kinship relations, where “duration is perceived according to the degree of current kinship relationships, the history of kinship relationships, and future possibilities of kinship relationships.”[22] To ensure that life continues to flourish on Earth, experiences of temporality should highlight the reciprocity and interdependence of various beings. Settler time, or the abstraction of an omniscient ticking clock, allows humans to disengage from their interdependence with other forms of life. Linear time, Whyte argues, creates a sense of imperilment, where we become urgently concerned with our own impermanence. This aligns with Allen’s insight that self-alienation follows from forgetting our lineage. The colonial state, functioning as a death drive, follows a linear path towards endless extraction and consumption of place. Within its structure, citizenship becomes a game that conflates consumption and survival; individuals must optimize themselves as both productive and consumptive subjects before they too are discarded. Linear time holds death as an imminent and permanent state. Simultaneously, the individualistic experience of linear time creates death; Whyte quotes a report written by Larry Merculief on Indigenous hunting practices in the Arctic, in which the latter explains that “if a hunter or others do not properly honour the creature that gives itself to the hunter for food, then its spirit will not return to take physical form.”[23] In other words, permanent death begins in the gaze of those for whom nature is already lifeless. Permanent death begins with disregarding ongoing natural life cycles. Cycles of birth, death and rebirth depend on the maintenance of mutual responsibilities of care between forms of life. In serving the linear abstraction of endless capitalist growth, settler time threatens the resilient living of natural cyclical temporalities.

Kinship time is applied at several levels in this sequence of IKWÉ. Grandmother Moon comes to Ikwé because she is responsible for ensuring that Ikwé tends to her own responsibilities towards life. She tells Ikwé that by producing light, humans are overshadowing the light that the moon has always gifted them. Light is often used to symbolize enlightenment and progress; here, Grandmother’s words could allude to humans’ linear pursuit of progress, which threatens the life cycles she has always cared for. This sequence holds the temporalities of kinship ties between Ikwé and the moon as her relative, and between Ikwé and the moon’s responsibility to ensure life cycles. Ikwé is responsible for ensuring that the moon can fulfill her responsibilities. She does so through another kinship relation: by bringing this film to us. Monnet (who also plays Ikwé) turns her gaze towards viewers to remind them that “It has never been more important to hear our grandmother’s stories.”[24] She invites viewers to ground themselves in the moon's cyclical temporalities beyond the film's time span. She presents a specific roadmap to ancestral knowledges: remembering all our past and present relatives, situating ourselves within greater webs of life, and recognizing the life-giving powers of our bodies and the cyclical rhythms they follow. Walking alongside past and future relatives, we recognize that life follows cyclical motions rather than a linear one. At the end of the film, Ikwé has undergone a full cycle herself. She started in the womb, where she met the powerful knowledge of her ancestors. She emerged, born from herself, affirming: “This is where I begin” (Figure 5). “Where” Ikwé begins is not a specific place or time. She begins where she last ended. Her life, like mine, yours, and the moon’s, is cyclical and continuous.

Figure 5. Ikwé begins again, born from herself, from IKWÉ, directed by Caroline Monnet (Winnipeg Film Group, 2009), 00:03:45. https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9.

To understand IKWÉ’s contribution to a resurgence of Indigenous worldviews, systems, and governance, we must perceive the continuity of its teachings. Its message transcends settler time because it is always relevant beyond screening time. In her call for a resurgence of Indigenous pedagogies, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson argues that resisting colonization requires following the teachings of the land.[25] To learn from the land, one must be immersed within the relational webs of life and the temporalities that form it. As Simpson declares: “The land must once again become the pedagogy.”[26] It is not enough to include land-based teachings in settler education systems, as it is not enough to include Indigenous Peoples in the modern nowness of settler time. The settler state pulls persistently towards individualism, forgetfulness, and, ultimately, death. Upholding kinship responsibilities to all forms of life entails refusing to consider colonial structures as permanent. It involves immersing ourselves in temporalities that transcend settler conceptions of past, present, and future. Simpson draws on the words of Jarrett Martineau and Eric Ritskes: “The freedom realized through flight and refusal is the freedom to imagine and create an elsewhere in the here; a present future beyond the imaginative and territorial bounds of colonialism.”[27] The work of Caroline Monnet transcends settler time by creating a space that enacts Indigenous temporalities, grounded in intergenerational knowledge and mutual responsibility for life systems, while simultaneously inviting the audience to find that space everywhere else.

Conclusion

In this essay, I aimed to celebrate Caroline Monnet’s contribution to the resurgence of Indigenous knowledges, and ways of being and becoming. I argued that Monnet’s film IKWÉ challenges settler time by honouring and enacting Indigenous notions of temporality based on relations of mutual care between forms of life. I conducted a close analysis of IKWÉ in two parts. In the first section, I discussed the film’s emphasis on the cyclical temporalities marking women’s relations with the moon and water, provided that cycles of rebirth and renewal oppose the colonial death drive. In the second section, I observed how IKWÉ represents kinship and relations of mutual responsibility between living beings that sustain the groundwork for movements of Indigenous resurgence. I argued that Monnet gazes boldly at the audience, with a necessary sense of urgency, transmitting the responsibility to care for natural life.

I am a settler from Tiohtià:ke or Mooniyang (Montreal); I live on Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk) territory, in continuous interaction with, and intricate embeddedness in its lands and waters. In writing this text, I aimed for my analysis to closely follow the narrative, images, and words of Caroline Monnet, as I acknowledge that Indigenous voices are systemically subordinated by those of settler researchers and scholars who hold privileged positions in the academy. I was also determined to follow Eve Tuck's recommendations in her critique of damage-based research. Tuck denounces the ease with which researchers have trapped Indigenous communities in narratives of victimhood and points to the importance of instead foregrounding their ongoing resistance, creativity, and futurity.[28] I oriented this paper towards celebrating and uplifting Indigenous temporalities and their significance in resurgence movements.

Endnotes

[1] IKWÉ, directed by Caroline Monnet (Winnipeg Film Group, 2009). https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9https://carolinemonnet.ca/#Ikw%C3%A9.

[2] Mark Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination (Duke University Press, 2017).https://muse.jhu.edu/book/69727.

[3] Paula G. Allen, “Who Is Your Mother? Red Roots of White Feminism,” in Provocations: A Transnational Reader in the History of Feminist Thought (University of California Press, 2015), 321–34. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520355958-020.

[4]Audra Simpson, “The State Is a Man: Theresa Spence, Loretta Saunders and the Gender of Settler Sovereignty,” Theory & Event 19, no. 4 (2016): 2. https://muse-jhu-edu.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/article/633280

[5] Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time, ix.

[6] Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time, ix.

[7] Salma Monani, Indigenous Ecocinema: Decolonizing Media Environments (West Virginia University Press, 2024).https://muse.jhu.edu/book/129927.

[8] Monani, Indigenous Ecocinema, 69.

[9] Susan Chiblow, “Relationships and Responsibilities between Anishinaabek and Nokomis Giizis (Grandmother Moon) Inform N’bi (Water) Governance,” AlterNative 19, no. 2 (2023): 283–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801231173114.

[10] Monnet, IKWÉ.

[11] Chiblow, Relationships and Responsibilities.

[12] Katsi Cook, “Grand Mother Moon,” in Words That Come Before All Else: Environmental Philosophies of the Haudenosaunee, (Native North American Travelling College/Haudenosaunee Environmental Task Force, 1999) 139.

[13] Chiblow, Relationships and Responsibilities.

[14] Monnet, IKWÉ, 02:00.

[15] Deborah McGregor, “Anishnaabe-kwe, Traditional Knowledge and Water Protection,” Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme 26, no. 3 (2008). https://cws.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/cws/article/view/22109.

[16] Chiblow, Relationships and Responsibilities, 285.

[17] Allen, Who is Your Mother?, 34.

[18]Allen, Who is Your Mother?, 37.

[19] Allen, Who is Your Mother?, 37.

[20] Monnet, IKWÉ, 01:20.

[21] Monnet, IKWÉ, 02:20–04:00.

[22] Kyle P Whyte, “Time as Kinship,” in The Cambridge Companion to Environmental Humanities (Cambridge University Press, 2021) 39–55.

[23] Whyte, Time as Kinship, 16.

[24] Monnet, IKWÉ, 02:20.

[25] Leanne B. Simpson, “Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg Intelligence and Rebellious Transformation,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3, no. 3 (2014). https://doi.org/10.5206/decolonization.v3i3.22242

[26] Simpson, “Land as Pedagogy,” 14.

[27] Martineau, Jarrett, and Eric Ritskes. “Fugitive Indigeneity: Reclaiming the Terrain of Decolonial Struggle through Indigenous Art.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3, no. 1 (2014), iv.

[28] Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (Fall 2009), 409–27.